Montrose VA 1958-1988: David Byrd

Anton Kern Gallery is pleased to announce its forthcoming exhibition David Byrd: Montrose VA, 1958 – 1988. The opening date, February 25th, coincides with the late-artist’s 95th birthday.

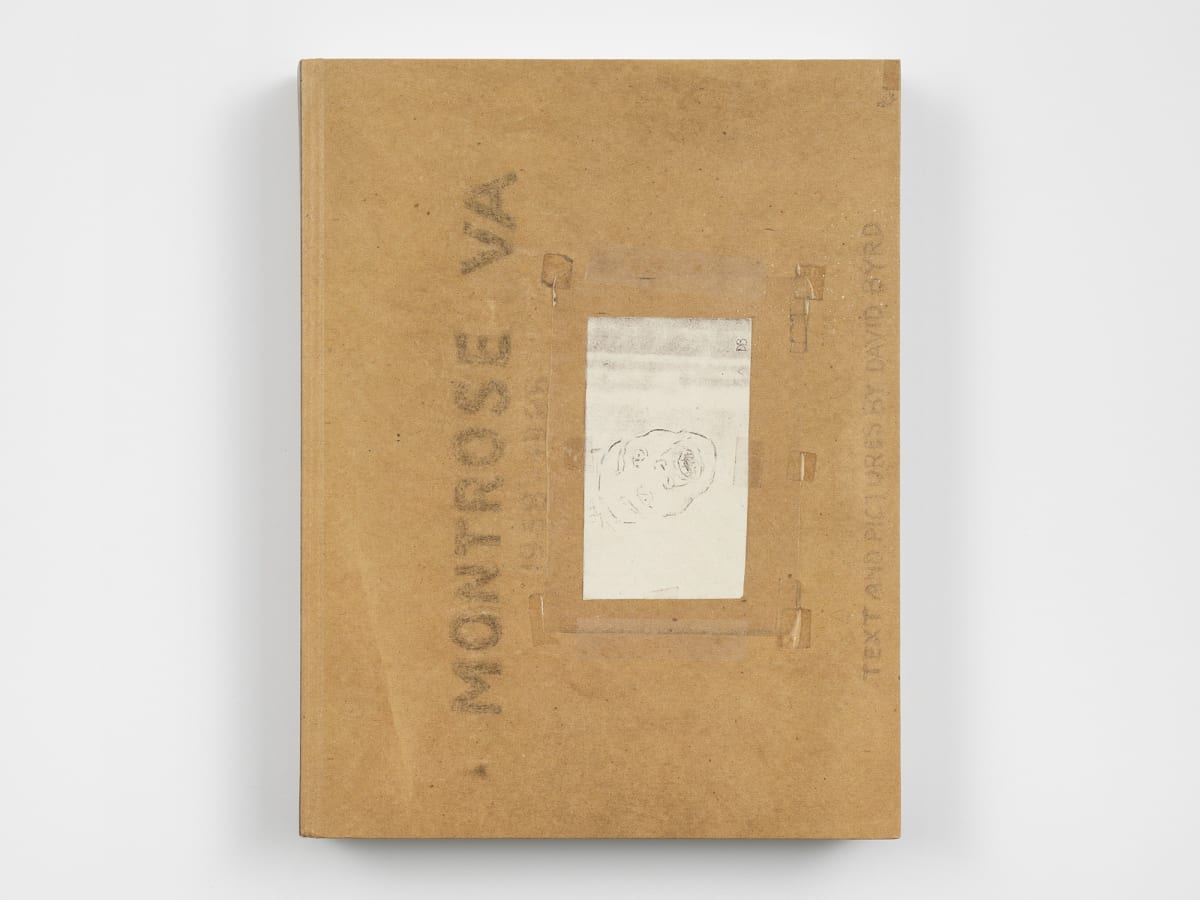

The exhibition centers around Byrd’s original manuscript, of the same title, chronicling his observations during his thirty-year career in the psychiatric ward of a VA hospital in Upstate New York. Compiled during the reflective period of his later years, the artist considered this handmade book his magnum opus. It serves as a crucial codex for understanding Byrd’s personal history, as well as his psychologically stirring oeuvre of paintings and works on paper. Select pages with handwritten texts, sketches, and colored pencil drawings will be displayed throughout the gallery in vitrines, accompanied by paintings, sketchbooks and other archival materials relating to this major body of work.

Byrd was intent on bringing his book to the public’s attention during his lifetime, however, he struggled to find the resources to publish. To honor the artist’s vision, the gallery has released a faithful replica of Montrose VA, 1958 – 1988, in collaboration with the David Byrd Estate and German publisher Hatje Cantz. The book is available for purchase at the gallery and on our online shop.

David Byrd was an American painter born in Springfield, Illinois, in 1926. His father, who suffered from mental illness, left the family when David was a young child. When he was twelve, his mother was forced by economic hardship to place him and his five siblings into foster care. In 1942, his mother gathered her children back to her in New York. Working as a ticket seller at a movie theater in Brooklyn, she could barely support them.

Byrd left home at age 17 to join the Merchant Marine, and was later drafted into the US Army during World War II. He used the GI Bill to enroll at the Ozenfant School of Fine Arts in New York City, where he studied for two years under the French painter Amédée Ozenfant.

Throughout the 1950s, Byrd worked a series of odd jobs-- including janitor, delivery man, movie house usher -- anything that would cover his bills while also (and more importantly) allowing him time to paint. From 1958 - 1988 he worked as an orderly in the psychiatric ward at the VA Hospital in Montrose, New York. Perhaps the regimented setting of a hospital was comfortable for him, having spent much of his young life within institutionalized systems. His daily experiences during this time inspired his most defining body of work.

Byrd was a keen observer of his surroundings who painted the people and situations he encountered, past and present, from memory. He also painted scenes from his daily commute-- including mountains, bridges, houses, gas stations, and shopping centers. In 1988 he retired, bought land in the Catskills, and focused full-time on painting until his death in 2013.

David Byrd’s work was not publicly exhibited until he was offered a solo show at Greg Kucera Gallery in Seattle, only a few months before his death at the age of 87. Since then, and through the establishment of the David Byrd Estate, his work has continued to be exhibited posthumously. The Estate is represented by Anton Kern Gallery.

-

David ByrdHospital Hallways, 1992

David ByrdHospital Hallways, 1992 -

David ByrdWoods Hospital, 1968

David ByrdWoods Hospital, 1968 -

David ByrdThe Cave, 1973

David ByrdThe Cave, 1973 -

David ByrdMan and Institution, 1993

David ByrdMan and Institution, 1993

-

David ByrdNurse Signing Orders, n.d.

David ByrdNurse Signing Orders, n.d. -

David ByrdNurse With Dietary Cards, 1998

David ByrdNurse With Dietary Cards, 1998 -

David ByrdGreenhouse at Hospital, n.d.

David ByrdGreenhouse at Hospital, n.d. -

David ByrdMan, 2008

David ByrdMan, 2008

-

David ByrdMontrose VA 1958 – 1988 book

David ByrdMontrose VA 1958 – 1988 book -

David ByrdMan Fatigued at Water Fountain, n.d.

David ByrdMan Fatigued at Water Fountain, n.d. -

David ByrdUnnatural Act on Ward, 1991

David ByrdUnnatural Act on Ward, 1991 -

David ByrdOuter World, n.d.

David ByrdOuter World, n.d.

-

David ByrdSoap and Man, 1974

David ByrdSoap and Man, 1974 -

David ByrdTwo Patients, 1980

David ByrdTwo Patients, 1980 -

David ByrdCard Players, 1989

David ByrdCard Players, 1989 -

David ByrdUnder Covers, n.d.

David ByrdUnder Covers, n.d.

-

4 Art Gallery Shows to See Right Now

Roberta Smith, The New York Times, March 24, 2021 This link opens in a new tab. -

David Byrd's palpable tenderness

Craig Taylor, Two Coats of Paint, March 4, 2021 This link opens in a new tab. -

Goings On About Town: David Byrd

Andrea K. Scott, The New Yorker, February 24, 2021 This link opens in a new tab.